Kirschenbaum, Matthew G., with Doug Reside and Alan Liu.

“No Round Trip: Two New Primary Sources for Agrippa.”

|

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, with Doug Reside and Alan Liu, See also Kirschenbaum, “Hacking ‘Agrippa’: The Source of the Online Text.”

|

| Matthew G. Kirschenbaum teaches in the English Department at University of Maryland, College Park, and is Associate Director of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH). His blog is at http://www.otal.umd.edu/~mgk/blog/; he may be contacted at mgk =at= umd =dot= edu. Doug Reside is the Assistant Director of MITH. Alan Liu teachs in the English Department at University of California, Santa Barbara, and is the general editor of The Agrippa Files site. |

It was June 2007, and I was awaiting page proofs for my book Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (MIT, 2008), which included extensive discussion of Agrippa (a book of the dead) and the circumstances under which William Gibson’s “Agrippa” poem within that work was released into the wild of the internet in 1992. Out of the blue, Alan Liu (the general editor of The Agrippa Files site) and I each received email from an individual identifying himself as “Rosehammer,” one of the three pseudononymous hackers credited in “Templar’s” original posting of the text of Gibson’s poem to the Mindvox BBS in 1992. Rosehammer had found and read a few pages of the manuscript for my book, which I had posted in advance to The Agrippa Files back in December 2005 (see “Hacking ‘Agrippa’: The Source of the Online Text”), and wanted to corroborate my account of “the hack” that let the text of Gibson’s poem escape onto the internet. Rosehammer then put me in touch with Templar himself, and subsequent email exchanges with both of them, as well as a phone conversation with Templar, allowed me to confirm and correct certain details of my account. The most notable correction concerned the location at which their bootleg video recording of Gibson’s poem as it scrolled up a projection screen had been made—not The Kitchen in New York City, as I had originally surmised, but the Americas Society in the same city—uptown instead of downtown, but on the same evening. (Brief excerpts from this recording were included in Re:Agrippa [Item #D16], a five-minute, experimental-video remix with additional material by Rosehammer and Templar that had already surfaced. But the provenance and other circumstances of Re:Agrippa were not then known.) This new information arrived in time to be included as an Appendix to Mechanisms. Rosehammer also promised to attempt to locate the original video recording of the Americas Society event, which has historical significance because—as he confirmed—it was in fact the source for the transcription of Gibson’s poem posted by Templar to MindVox that night on December 9, 1992. Rosehammer did eventually locate and send it, but not in time for my book’s publication.

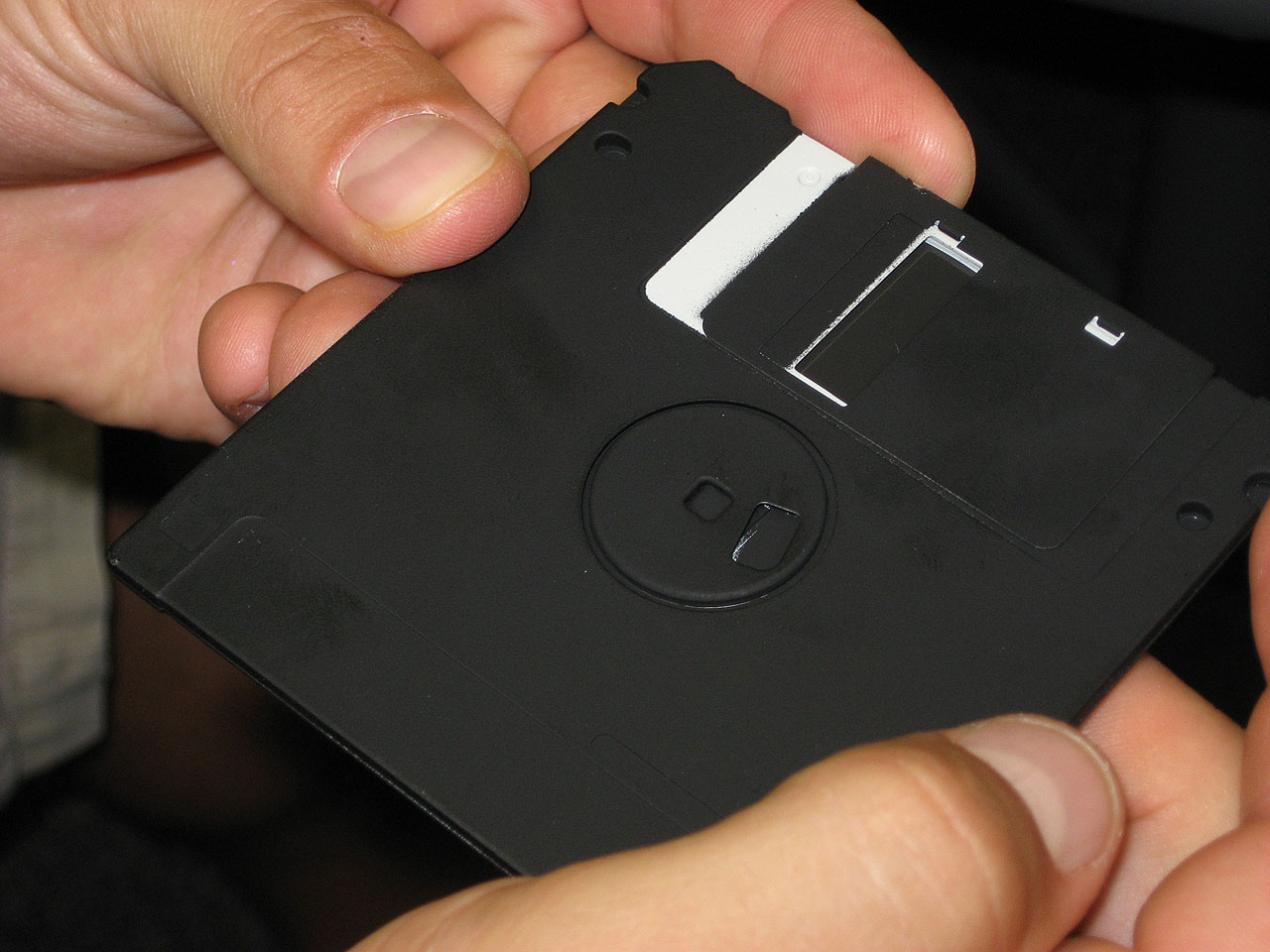

Then, half a year later in January 2008, Kevin Begos, Jr. (Agrippa’s publisher) contacted Alan Liu with an offer from Allan Chasanoff, a collector in Manhattan who owned an original copy of Agrippa with the diskette containing Gibson’s poem. Chasanoff was willing to lend his disk to a scholarly effort to “copy” and examine the content of his mint-condition 1.4 Mb diskette (plus a mysterious second 800 Kb diskette described below), which he presumed contained the software that displayed the poem and then famously encrypted it to make Gibson’s words disappear after being read just once. A “run” of this software—the scrolling display of the poem accompanied by its disappearance—had not been seen in public since that night at the Americas Society in 1992. Alan, Kevin, and I decided the disk should come to the University of Maryland, College Park, where we would be able to draw on technical expertise from a new Digital Forensics Lab on campus, as well as the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH) in the person of Assistant Director Doug Reside. Through a process of trial and error, we were able to obtain a complete “disk image” of the disk (that is, a bit-level copy) and then mount that copy in a Macintosh System 7 “emulator,” a software duplication for current machines of the functions of the original operating system on which the 1992 disk ran (definitions of disk image and emulator). This allowed us to run (and rerun) the Agrippa diskette at will by spawning multiple copies of the disk image and running each to its death (encrypted disappearance) through the emulator. (The technical process is detailed below.)

As a result of these two fortuitous events—the recovery of vintage footage from the Americas Society event and mint code from Agrippa diskette, the following new archival resources were made available on December 9, 2008, on The Agrippa Files site—the sixteenth anniversary of the so-called “Transmission” event or public debut of the Agrippa book and Gibson’s poem in it:

- Bootleg Video of Gibson’s “Agrippa” Poem as Publicly Unveiled on Dec. 9, 1992

- Item #D48: Video derived from DVD (VOB-formatted) files, which in turn were derived from a copy of the ¾” videotape recording surreptitiously made by Rosehammer at the Americas Society unveiling of Agrippa on December 9, 1992 (presented as Google Video for rapid access or QuickTime video for higher quality on The Agrippa Files site).

- Item #D49: High-resolution photographs of the original video cartridge containing the above recording.

- Disk Image Code and Emulated “Run” of “Agrippa” Poem from Original 1992 Diskette

- Item #D50: Disk image (bit-level copy) created from the collector’s (Allan Chasanoff) original 1992 Agrippa diskette using the “dd” copy process. (See details of technical process below.)

- Item #D51: A video capture of a complete “run” of Gibson’s scrolling “Agrippa” poem made from playing the disk image on a Mini vMac emulator with a System 7 book disk (presented on The Agrippa Files as Google Video or a higher-quality QuickTime video). (Also: still images from the running emulation.)

- Item #D52: High-resolution photographs of the collector’s 1.4 Mb, 3.5″ diskette (plus the mysterious 800 Kb 3.5″ diskette that accompanied it).

We were able to contact William Gibson, and he gave permission for the emulation of his running poem to appear on The Agrippa Files. These materials also appear with the consent of Kevin Begos, Jr., “Templar,” and “Rosehammer.” Robert Maxwell from the Digital Forensics Lab at the University of Maryland provided assistance and expert advice; Bini Tecle and Allan Rough at Maryland assisted with the playback and digitization of the video tape. Our deepest thanks to all of these individuals for facilitating and encouraging this next stage in Agrippa’s ongoing “transformission.”

Footage: The Bootleg Video

In Mechanisms, I furnished two competing first-hand accounts of how the text of Gibson’s poem came to be on the MindVox bulletin board in the early morning hours of December 10, 1992. According to one of these, the text was essentially filched by someone from inside the project. This scenario has never been suggested by other than a single individual. The other account holds that the source of the widely circulated online text of the poem is a transcription from a surreptitious video recording made at one of the events comprising”The Transmission” on the evening of December 9. This latter account is now substantiated by the narratives of Templar, Rosehammer, and the existence of the recovered tape from the Americas Society event, which we present on The Agrippa Files in its entirety—thus establishing the events at the Americas Society as the critical nexus in the migration of Gibson’s text onto the internet.

As described in Mechanisms, Templar, Rosehammer, and Templar’s significant other, “Pseudophred,” were tapped by a member of the faculty at New York University’s Interactive Television Program to provide technical support for Kevin Begos at one of several public unveilings of Agrippa occurring the night of December 9, 1992—events collectively dubbed “The Transmission” by their orchestrators. The technical issue was how to capture the input of Begos’s Powerbook 180 computer for big-screen projection. Templar and company accomplished this by using a Hi8 video camera to get a shot of Begos’s computer screen while routing the video output to a Sony VPH-1041Q projector. Unbeknownst to Begos and others responsible for organizing the event, however, Templar also had a blank cassette in the camera on which he recorded an hour’s worth of footage, including the complete “run” of the poem that became the basis for the subsequent transcription of the text. This original Hi8 recording has never been located. What Rosehammer did recover, however, was a ¾”-tape duplicate of that recording, made in NTSC format and labeled “AGRIPPA—[Templar’s] VIEW.”

There is approximately one hour’s worth of footage. It divides into four basic segments:

- First, for five minutes, a welcome and introduction to the evening by Laura Blum, Director of Programs at the Americas Society. She contextualizes the event as part of their “Cyber Readings Series,” which the previous month had featured Gibson himself. Blum describes the poem in Agrippa as “Gibson’s withering computer disk story of the withering of his father.” She offers self-effacing remarks about her own lack of technical prowess, which have the virtue of articulating the hardware specifics for the festivities.

-

Next comes roughly twenty minutes of interview between Kevin Begos and Karen Benfield, a producer with the Wall Street Journal Television Report (figure 1). Begos offers new insights and information in the course of the conversation, which by itself is a valuable addition to the available primary sources on Agrippa.

- Then we have the onscreen “run” of the poem, which begins after a few minutes of technical fumbling during which Begos continues to take questions. The run of the poem on the big screen is accompanied by a synchronized recording of well-known comedian and new-technology enthusiast Penn Jilette reading the text. This too takes just about twenty minutes.

- Afterwards, Begos returns to the podium and takes additional questions. This fourth and final segment of the recording is cut off after ten minutes and so is incomplete, at least on the ¾” version of the tape.{1}

Benfield’s interview with Begos covers much of the predictable ground. She inquires into the origins of the Agrippa project, its significance as an “ebook,” the implications of its disappearing status for collectors and museums, and the rumors that the work contains a virus. Some important new details and insights into the conception and production of the overall work (the limited-run Agrippa art book containing in its last pages the diskette with Gibson’s poem) emerge. However, because the camera remains focused on Benfield almost the entire time that the two are seated together—in a disconcerting reminder of what Gibson’s poem calls “the mechanism”— all we have is Begos’s disembodied voice. Among the new information to be gleaned:

- The Agrippa project, which had been discussed for several years, grew out of Gibson and Ashbaugh’s friendship and desire to collaborate, specifically as they conversed about it during a night on the town while attending an art fair in Barcelona.

- About a year and a half previous to the December 1992 unveiling of Agrippa at the Americas Society (i.e., 1990), Begos had suggested the idea of a “book that destroys itself after one reading.”

- For his part, Gibson had discovered the eponymous KODAK Agrippa photo album at his father’s house in West Virginia about a year earlier (also presumably 1990).

- Begos mentions that several museums and collectors apparently expected to receive copies of the disk that would not self-destruct, but he, Ashbaugh, and Gibson “stuck to their guns.”

- There is a notable comment about the projected difficulties of finding a Mac that can run the System 7 operating system in “twenty years”: you would have to “hire a technical crew to reconstruct such a primitive computer language.”

- Begos confirms that the encryption that makes Gibson’s poem disappear is based on an RSA algorithm, a one-way encryption key that takes each line of the text and enciphers it as it scrolls by. Hackers, Begos tells us, had bragged about breaking the code on various BBS bulletin boards, but “nobody has gotten hold of it yet.” (It is interesting in this context that the imminent release of the text onto the network was similarly a kind of “one-way” ticket, in that there was no way to reverse the text file’s near-instantaneous propagation.)

- Begos recounts an incident that took place soon before the Americas Society event on the evening of December 9, 1992, when Laura Blum took a call from a “Bud Cook” in Ontario that caused “a brief panic.” This individual claimed that there was a virus in the transmission program and that Begos had to call him to get the modem numbers changed or “the whole thing would collapse.” The episode helps explain something of the nature of “the Transmission” itself, which was neither originating from nor received at the Americas Society. There, the diskette was running locally, without the need to involve phone lines and the internet at all. The actual “transmission” was timed to start at 7:30 pm (EST), involving planned sites in Tallahassee, Florida, Kansas City, Missouri, and elsewhere. As Begos puts it in the recording, he realized the event was a “big flag” for the hacking community and that he and “Bill” had decided they “were not going to make it that easy” (by sending out clear-text over a publicly advertised phone line).

- About Ashbaugh’s etchings, Begos comments that Gibson was fascinated by the work, which was inspired by “scientific DNA scans” (the now visually iconic analysis of DNA strands through agarose gel electrophoresis). Ashbaugh’s copperplate aquatint etchings were originally created as DNA “portraits” based on a sample of an anonymous collector’s hair. Agrippa, as Gibson and Asbaugh initially conceived it, would be a futuristic scrapbook, vintage “twenty or thirty years in the future,” whose DNA samples would allow one to reconstruct a complete personality—an idea, Begos notes, that Gibson had already been exploring in his fiction (for example, Neuromancer’s Dixie Flatline construct).

- Begos comments that the plurality of the different experiences that people will have as they experience the work in different places and settings means that everyone will have “slightly different” memories of it. Gibson, he says, summed up that idea by suggesting that his poem (once encrypted) is not really destroyed. It is just transferred from a computer to human memory.

- Finally, bibliographic details about editions and prices emerge. Begos states that the Deluxe edition of 95 copies is almost sold out and that a small-format edition of 350 copies is planned. He mentions the possibility of a Japanese edition (never to our knowledge realized).

When Benfield’s interview with Begos concludes, the lights darken and the main event occurs: a complete run of Gibson’s poem from the diskette as played on Begos’s computer and projected on a screen. (A quick reminder about the technical setup is in order: Templar and Rosehammer were asked to the event to engineer the big-screen projection, not to create a recording. They used a Hi8 video camera to capture Begos’s laptop screen and throw it to the big screen at the front of the room. Unbeknownst to Begos, et al., however, Templar had also loaded a blank tape into the camera and recorded the video signal.)

As shown in the footage, Begos’s Powerbook and its System 7 desktop appears on a table at the front of the room beside the screen. Begos has opened the folder containing a file called AGRIPPA. There is a false start of some kind, and then Begos double-clicks the program again. We briefly see the wristwatch cursor; then his AGRIPPA file opens full screen. As Gibson’s poem begins to move up the screen, Penn Jilette’s recorded voice immediately cuts in with a recitation, but with the “I” of the first line truncated. Therefore, the audio begins, “[H]esitated before opening. . . .” There is a relatively long pause in the recording after the poem’s first three lines, then Jilette resumes. After the line, “‘Papa’s saw mill, Aug. 1919,'” there is an unidentified disruption in the circumstances at the location of Jilette’s reading, and Jilette’s recorded voice, rather frantic, is heard to say: “No, we started we can’t go back.” “Did you get that first part on tape?” “We’re okay.” “Do you want to start again?” “Okay, let’s go.” He then resumes his reading, backing up a few lines: “Then he glued his Kodak prints down.” (Nervous laughter ensues from the audience at the Americas Society.)

The actual text of Gibson’s “Agrippa” poem as it scrolls up the screen in the recording (from the ¾” tape) is not quite legible. One can make out the shape of words and lines. Given Jilette’s voice-over (and knowledge of the poem), one has no problem recognizing the text in those shapes. But the text would be difficult to transcribe, particularly in regard to punctuation and any intricate typography of the sort: “can be made out this cryptic mark: / H.V.J.M.[?]”. Rosehammer speculates that the ¾” tape was actually recorded at a yet more distant remove by pointing a video camera at a monitor playing back the original Hi8 recording. According to Templar, “We recorded onto the camera in Hi8. When we got back to the shop, we used a double Hi8 editing deck for playback. It was crystal clear. Any errors in the transcription are mine, not the fault of the recording equipment.”{2} The complete run of the poem takes a little under twenty minutes.

At the end of the screening, the lights at the Americas Society come back up. Begos goes to the podium for more questions. He immediately explains why the blooper near the beginning of the recording was left intact: “the best thing that sums up project are the rough edges”; “nothing worked right along the way”; there were “astounding problems.” He, Gibson, and Ashbaugh all agreed that “rough edges was the way it should be, instead of trying to make something perfect and seamless and flawless.” Next comes his most startlingly prescient comment of the evening: “I expect Gibson’s fans to be selling bootlegs, videotapes of a fuzzy screen,” like “rock and roll bootlegs.” This comment anticipates precisely the nature of the “hack” that would follow within hours. A few more minutes of question and answer, and then the tape cuts off. Templar explains, “If I remember correctly, I stopped recording at that time because someone came over to the table and I didn’t want him to see the pretty red light.”{3}

What were Rosehammer and Templar to do with their bootleg video? In 1992, of course, uploading the actual footage to the Internet would have been impossible to contemplate from the standpoint of storage and bandwidth (let alone with available means of playback). Therefore, just the text of Gibson’s poem was manually transcribed and posted to the MindVox BBS as a plain-text ASCII file, which allowed it to propagate rapidly across bulletin boards, listservs, newsgroups, and FTP sites. (I reconstruct this chain of events in Mechanisms; see also excerpt on this site) Today, however, the footage would have undoubtedly been posted direct to YouTube, Google Video (chosen for The Agrippa Files because it allows uploading of longer videos), or some other streaming media site, eliminating the need for scribal mediation. It is worth remarking, then, that the brilliant act of low-tech, manual, and analog transcription through which Rosehammer and Templar accomplished their “hack” of Agrippa (analog video copied by hand as text) ineluctably dates Agrippa as the product of a certain technological moment at the cusp between old and new media. The camera shutter falls irreversibly, as Gibson’s poem says, even as we retain a residual memory—like a retinal after-flash—of olden days when the Kodak, Hi8, or handwritten moment was the word. It is in homage to such a layered history of media—specifically, the media that bring us Agrippa—that on December 9, 2008, we debuted on The Agrippa Files the original footage of the work’s rendering at the Americas Society event on December 9, 1992. After all, The Agrippa Files site— whose platform is based on the WordPress blog system and, now, also online video streaming platforms such as Google Video—represents yet another layer of new media (so-called “Web 2.0”).

One last note: for reasons which are unknown, the cassette case housing Rosehammer and Templar’s ¾” video based on the America’s Society event labeled on the outside: “RE:AGRIPPA.” This title refers to a video artifact (Item #D16) produced by Rosehammer in 1993 by remixing samples from the original 1992 footage and adding other video and audio material meant to comment on Agrippa—all styled in a raw, brash “experimental video” mode. Re:Agrippa, which was available on the Agrippa Files well before the discovery of the original Americas Society recording on which it was based, includes a few heavily processed moments of footage from the original recording. Re:Agrippa was apparently intended as Rosehammer’s own oblique commentary on the significance of Agrippa and its hack. As such, it stands as an early and still striking example of the original work’s “transformission.” Nevertheless, it is the actual cassette housing the ¾” tape that gives us access to the unedited ur-footage from the Americas Society event on December 9, 1992. (There are a couple of other markings on the case of the ¾” tape that are perhaps of interest as well: on the front we see “Rosehammer” and what appears to be a copyright symbol, certainly an interesting gesture in light of the casual attitude toward intellectual property otherwise exhibited; and on the spine of the case there is a symbol or glyph that appears to be a stylized rose and hammer, crossed within a circle.)

“The Revealed Grace of the Mechanism”: The Disk Image and Emulation

While the text of the “Agrippa” poem is widely available on the Web, including on Gibson’s own official Web site (the persistent availability of this text as a notoriously volatile digital object is one of the paradoxes that drives my arguments in Mechanisms), to the best of our knowledge the poem has not been seen in its entirety in its original incarnation since the evening of “the Transmission” in 1992—an event here referred to (with allusion to the “Straylight Run” in Gibson’s novel Neuromancer) as the “run.” It certainly has not been run publicly in this fashion. While the significance of the original interface and behaviors of the digital poem may be slight for those interested in it strictly for its literary aspect, as a software artifact the born-digital poem speaks powerfully to the experience of “aura” in electronic environments—in other words, the qualitative difference between reading the text as an ASCII transcription and encountering it as a running, functional program with unique affordances and behaviors. The experience is perhaps roughly comparable to those who read a poet such as William Blake only in the typographically pristine precincts of modern literary anthologies versus those who seek out reproductions of Blake’s original illuminated etchings, where word and image commingle in casual splendor.

Indeed, a digital emulation is something very much like what textual scholars, working in the realm of manuscripts and printed matter, would call a “facsimile edition.” An emulator is a program that simulates on a contemporary computer a particular, usually older hardware environment, allowing one to execute legacy code through a virtual (software-implemented) chipset and operating system. Because of this, we are actually running (in software parlance: “interpreting”) the Agrippa code, not merely mocking up its appearance and behaviors. However, there remain ineluctable differences and distances from the original, starting with the ergonomics of the physical computer itself, the fundamental disparity of the contemporary graphical desktop environment, modern skins and chrome, the distraction of other windows and applications, and so forth. Differences can also manifest at the level of processor clock cycles and other ineffable elements of the original system (which, in a well-known example, make emulations of older video games on modern systems sometimes unsatisfactory because timing is so crucial in the experience of digital gaming). Surely, the most important difference is that with the emulator we used for the “run” we can view Gibson’s poem repeatedly, any number of times, thereby eliding the foundational premise of the original work: its read-once-only evanescence. Yet one of the ironies of the process is that we have to feed the emulator a new copy of the disk image each and every time we run the program, since it does indeed encrypt the data exactly as it was designed to do. Each individual instance of the disk image is only useable once.

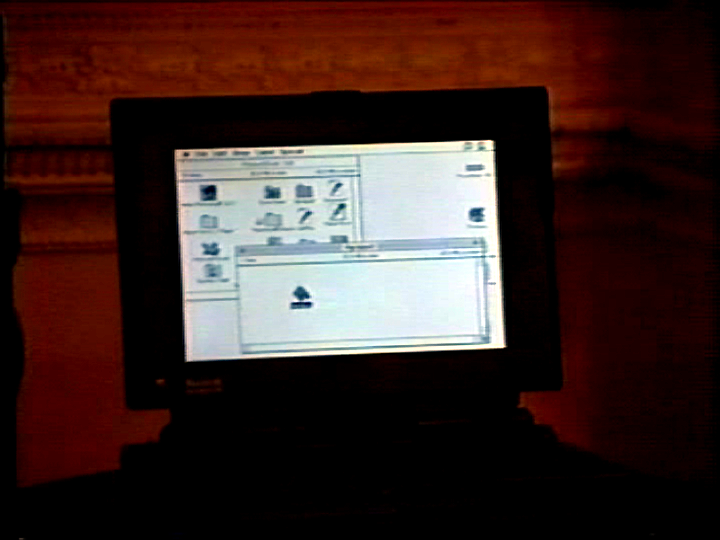

Our process was as follows. University of Maryland received two 3 ½” diskettes from the collector, one formatted for 1.4 Mb and one for 800 Kb. The 1.4 Mb item appeared to be a stock Maxell, doubled-sided double-density diskette. (The diskette included with the New York Public Library copy of Agrippa is of this same type.) The 800 Kb item, meanwhile, was apparently spray-painted black (sliding the shutter at the bottom of the disk revealed white beneath). We began with the 1.4 Mb diskette. (The personnel at Maryland consisted of Doug Reside of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, Rob Maxwell of the Office of Information Technology, and myself.) Flipping the write-protect switch to “on,” we inserted the diskette into an internal floppy drive on a desktop machine in the University of Maryland’s Digital Forensics Lab running a modified version of Debian Linux. Using the standard data definition “dd” application, we created a bit-level copy or image of the disk. (A bit-level image records every individual bit of information on an instance of storage media, not merely the items in the file allocation table.) We then used the “dd” application to recopy the data from the 1.4 Mb image to another floppy disk. Although the latter disk mounted on several legacy machines roughly contemporary with the poem (each running various versions of the System 7 Mac operating system for which the 1992 diskette was originally designed), the Agrippa program never successfully ran on any of the systems.{4} (In making these attempts, we were at pains to consult the original Agrippa documentation available on The Agrippa Files site.) Occasionally (and seemingly not according to any reliable pattern), the drive would spin for a while or a white box would appear, but quickly thereafter the program would crash. For a time we thought our efforts had failed—or perhaps the original disk had been used after all, the program now encrypted and thus irretrievable. Finally, however, we succeeded in launching the program on the vMac emulator running a copy of System 7.0.1.{5}

When we opened the Agrippa program in the emulator, we first saw a blank white screen, followed by the frontispiece image, which stays visible for some twenty-five seconds. Then the opening lines of the poem appear, followed during the next eighteen minutes or so by the auto-scrolling of the rest of the text up the screen. At the conclusion, a few blocks of encrypted text wash across the screen. Then the program terminates and the viewer is dumped back out to the emulated Mac desktop.

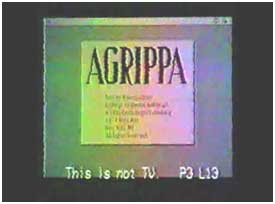

The blank white screen in the emulation in fact should appear as the credit and copyright notice that was visible on the screen in the Americas Society video, and also in an edited frame from Rosehammer’s Re:Agrippa.

Credit and copyright notice at beginning of bootleg video from the Americas Society event on Dec. 9, 1992. (A blank screen appears instead in the emulated run of the diskette.) |

Why this notice is blank in the emulation, we don’t know. Perhaps there is a font missing from the emulator’s boot disk, or perhaps the copy of the program that we imaged was incomplete in some way. Maybe it is only appropriate that our emulation continues the tradition of “rough edges” that Begos mentioned at the Americas Society.

A collation of the text from the original Agrippa program with the text of the poem as it circulates on the internet reveals very little in the way of variants. The most significant is the presence of an opening set of quotation marks at the very beginning of the poem, so that the first line in fact reads:

“I hesitated

There is no corresponding set of closing quotation marks. Whether these opening marks are merely accidental, vestigial, or part of some additional narrative frame for the text (deliberately broken or otherwise) we do not know. Beyond that, there are a few other minor variations in punctuation and capitalization. The lineation of the text on the Web is also generally faithful to the original. It would appear that Templar’s manual transcription of the text was remarkably (almost preternaturally) accurate.

There are two audio effects as the poem plays, something I have not seen previous mention of in the commentary about Agrippa. We hear the sound of a camera shutter clicking at “the shutter falls” (6:05) and the sound of a gunshot at “I swear I never heard the first shot” (7:33). These sounds are also audible on the Americas Society bootleg video if one listens for them.{6} The audio effects seem surprisingly literal and arbitrary, as though this dimension of the work did not develop beyond a tentative mimesis. They also invariably startle, given the otherwise serene and stately presentation of the poem scrolling up and off the screen.

We also attempted to disk-image the painted 800 Kb floppy using the “super drive” on a Macintosh Powerbook G3 (Wallstreet edition). 800 Kb floppies require different physical hardware in the drives than their 1.4 Mb successors. This Powerbook had successfully imaged other 800 Kb disks using its Macintosh Disk Copy utility, but given the unique copy protections associated with the Agrippa diskette, mounting the diskette on a system running any version of a Macintosh OS seemed too dangerous too attempt (we didn’t want to risk triggering the encryption ). So we opted instead to create the disk image while running a live CD of Ubuntu 5.10 on the Powerbook. We were unsuccessful, although we suspect this was because of driver incompatibilities with the “super drive,” as later attempts to image other 800 Kb diskettes using the Ubuntu Live CD also failed. Our best guess is that the 800 Kb, painted diskette may have simply been a prop, perhaps intended for display with one of the project’s prototypes. We believe it is unlikely that it contains any data relevant to Agrippa.

We finally want to emphasize that we did not in any way “hack” the Agrippa program to accomplish what we describe here. This is important not mainly for legal or ethical cover, but because the language of hacking would obscure what are in fact well-established, open procedures in the digital preservation and forensics community. Hacking has had a colorful place in Agrippa’s lore. Indeed, I would hold that Templar and his colleagues can indeed claim credit for a “hack” of sorts—albeit one that was not fundamentally computational in nature—when they were able to transcribe Gibson’s poem from their bootleg video. But the term “hacking” would lend our work an aura of derring-do that is both deceptive and distracting.

No Round Trip

And surely that is the “revealed grace of the mechanism,” to use the language of the poem: that there are no round trips. In a view with which Alan Liu concurs, I believe that The Agrippa Files site on which we can now offer both the new primary sources (the bootleg video and the disk image/emulation) is as much an extension of the still-dilating performance of Agrippa as it is an “archive” or “repository,” terms that encourage too much detachment from the realities of the network environment in which the work is now irretrievably situated. After all, the “hack” wasn’t only about transcribing a single instance of the text; it was about enacting a modal shift in its semiotic nature, thereby allowing it to propagate endlessly and effortlessly. Both the new “primary sources” we offer are in fact exquisitely mediated, not only through layers of file formats, compression algorithms, and virtual machinery, but also through the shifting contours of the network itself, which, in the era of The Agrippa Files (originally created in 2005), brokers very different relationships and transactions than it did sixteen years ago in 1992 on the eve of the first release of the then groundbreaking NCSA Mosaic Web browser. If disciplines such as textual studies and cultural criticism teach us anything, it is that our representations are always one-way keys, not to the past but the present.

“In short,” Alan Liu has observed, “Agrippa was for all practical purposes a self-sustaining circuit of event driven/event-producing information ‘about’ Agrippa (‘information about information,’ Shoshana Zuboff characterizes such phenomena in her In the Age of the Smart Machine) whose ‘being,’ which is to say doing, far exceeded that of any actual instances of the work issued or seen.”{7} This new set of materials scarcely alters that dynamic. Indeed, there are at least two primal artifacts that remain beyond reach. The first is the source code for the encryption program, a few scraps of which survive in hard copy and are viewable amongst the materials on The Agrippa Files site. The second is the electronic manuscript of the poem itself, marooned on whatever computer Gibson originally wrote it on, wherever that machine is now (if it even still exists as functional hardware). Nonetheless, these materials do offer a kind of closure to anyone who, like me, has ever stumbled across the text of Agrippa on the open net and wondered, but how did it get there? Those mechanisms are now known and documented. So we take satisfaction in the release of these new “Agrippa files” (as it were) to scholars and fans alike, and we marvel that after sixteen years in the digital wild a frail trellis of electromagnetic code once designed to disappear continues to persist and to perform.

1. The first couple of minutes of the original tape also include introductions between persons at the event and individuals whose names correspond to the real-world identities of Templar and Rosehammer as discovered through my correspondence with them. Out of respect for their privacy, this footage is not reproduced here.

2. Email from “Templar” to Kirschenbaum, Fri, Oct 19, 2007 at 11:10 AM.

3. Email from “Templar” to Kirschenbaum, Fri, Oct 19, 2007 at 11:10 AM.

4. The Info window on the Agrippa program captured in the image revealed its Creation date as Wed., Oct. 7, 1992, 10:35 pm.

5. The image files for this version of the operating system, the only one on which the program seems to work reliably, can be downloaded from Apple’s Web site.

6. Interestingly, the line about the camera shutter also receives synesthetic treatment in Rosehammer’s Re:Agrippa video. There, at 5:25, for a split second, we glimpse the text from the poem: “A lens / The shutter falls / Forever” This moment, a single video frame, seemingly literalizes the act of still photography that is a backdrop for the Agrippa concept.

7. I quote from an unpublished paper delivered at Stanford on January 12, 2007 entitled “The Agrippa Process: Agrippa (A Book of the Dead) in the Age of Web 2.0.” Emphasis is in original.